Hydrant History: Standardizing Wet-Barrel Hydrants

After its first major fire in 1851, a San Francisco foundry began casting wet-barrel hydrants. A century later, Greenberg’s collaboration with water districts all over California had forever united hydrant engineering with municipal water management. But that didn’t mean the water providers and customers could live happily ever after. First, we needed assurance that the products storing and purveying water were safe, and that they functioned as a cohesive system. In short, the water industry needed regulation.

For more about the advent of wet-barrel hydrants, see our previous post, “The California Hydrant.”

By the mid 1950s water networks had grown exponentially, and industry voices were calling for a set of standards on hydrants and hydrant accessories. The American Water Works Association (AWWA) stepped in: in 1958, they began issuing standards and guidelines that would ensure new products fit seamlessly into California’s rapidly growing infrastructure. Today, ANSI/AWWA C503 is the standard that describes minimum specifications for wet-barrel fire hydrants. These specifications encompass materials, design, coating, color schemes and accessories. Because many hydrants are connected to drinking water systems, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF) also began regulating the types of materials connected to water networks. By this time, the public had been alerted to the toxicity of heavy metals like lead, an element previously used in pipes and hydrant components.

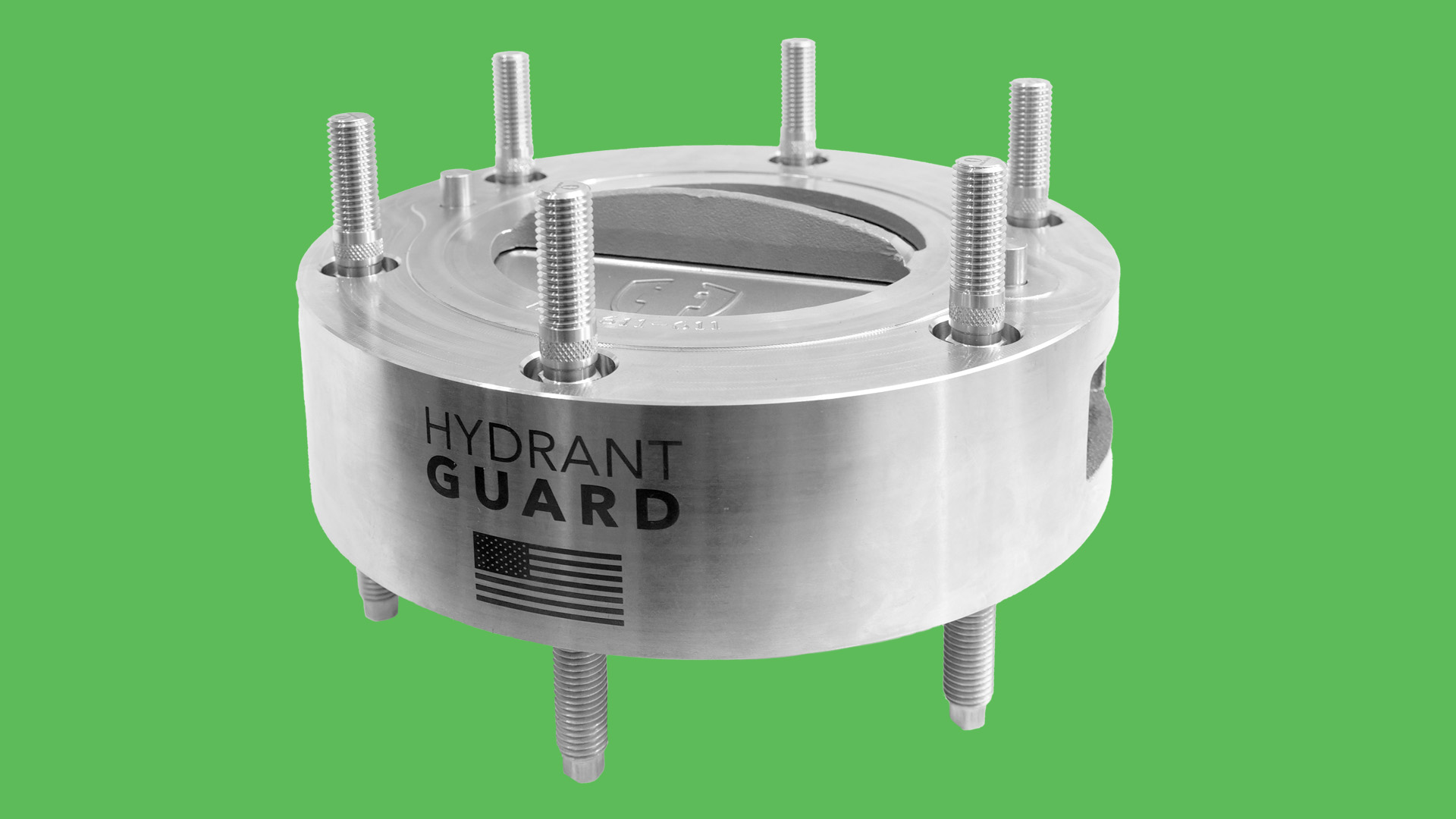

With standards and regulations in place, wet-barrel hydrants were ideal candidates for California’s meshwork of pumps and pipelines. With all mechanical parts above ground, they were easy to install and use, allowing outlet valves and nozzles to operate independently. But there was one drawback: wet-barrel hydrants can be sheared from their mounts, and without an integrated automated waterflow shut-off mechanism, the result is water surges (also known as geysers). Break-off check valves like Hydrant Guard have since become vital accessories to wet-barrel networks. On impact, check valves shut water off from the main after allowing the hydrant to cleanly detach from the mount, preventing huge amounts of non-revenue water loss after a shear, and protecting the people, property and systems nearby.

Supplying water and fighting fire have an entangled history: keeping people healthy and safe requires systems that supply clean water to drink, as well as extinguish fires. Modern fire hydrant systems are a culmination of years of innovations in water distribution and fire fighting. From clay to wooden and, finally, steel water mains; from mechanical pumps to bucket brigades, a check valve is another solution in a long line of inventions aiming to make our lives healthier, cleaner and safer.

Learn more about fire fighting, fire hydrants and municipal water providers in our Hydrant History series